Explore More

What Works for Boys: Rethinking Mental Health Support for the Next Generation

Explore research revealing why group support fails young men, how cultural differences matter and which mentor-led mental health strategies succeed

Three out of four boys aged 15 to 17 find group activities helpful for their mental health. By the time they reach 18 to 24, only three out of five still feel the same way. That 15-point drop tells you everything about why your son, nephew or the young men in your company might be struggling – and why throwing more of the same support at them won’t work.

The data comes from Surgo Health’s Youth Mental Health Tracker, the first comprehensive analysis of how boys and young men actually experience mental health support in America. The findings challenge every assumption about why young men don’t seek help.

They’re Not Refusing Support – They’re Tuning Out Systems That Don’t Work

‘We talk a lot about a mental health crisis among youth, but we rarely ask boys what they need or why they’re pulling away,’ said Dr Sema Sgaier, CEO of Surgo Health. ‘The issue isn’t indifference. It’s invisibility. The systems built to support young people weren’t built with boys in mind.’

The report reveals a pattern that high-performing men will recognise from other areas of life: when tools don’t deliver results, people stop using them. Boys aren’t avoiding help because they’re stoic or stubborn. They’re abandoning support systems that feel irrelevant to how they actually experience emotional challenges.

Consider the digital disconnect. While 74% of adolescent boys and 76% of young men have used social media to learn about mental health, only 60% of adolescents and just 43% of young men found it helpful. Mental health apps show the same pattern: widespread adoption but poor satisfaction rates.

The Support That Actually Works – And When It Stops Working

Group-based support works brilliantly for teenage boys, then loses power as they transition to adulthood. The data shows why: participation in religious or faith communities drops in perceived helpfulness from 64% among 15-17 year olds to 48% among 18-24 year olds. Community volunteering similarly falls from 68% to 56%.

Research from BMC Public Health confirms that peer support groups create effective environments for boys by reducing stigma and enhancing self-esteem. The key insight is timing – these communal connections weaken precisely when young men need them most.

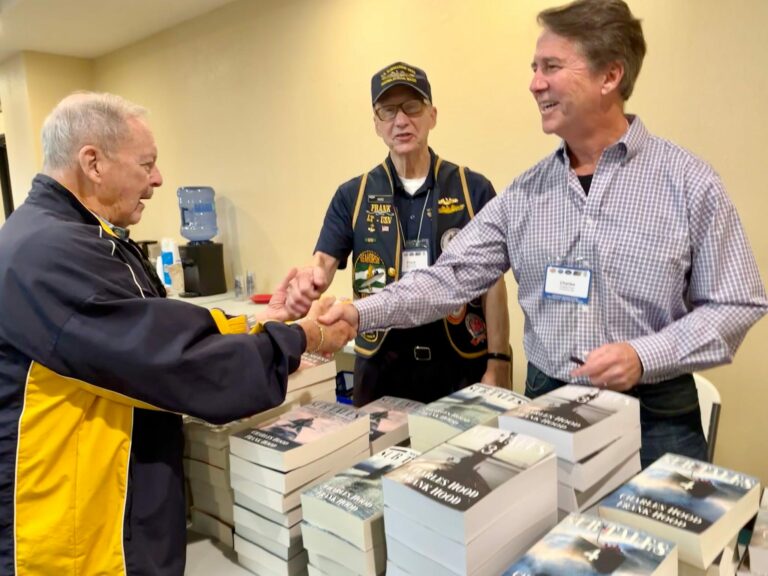

Successful programmes that maintain engagement into young adulthood share common elements. Boys to Men Mentoring focuses on volunteer mentors who provide consistent guidance through the transition to adulthood. The Steve Harvey Mentoring Program uses positive male role models from business and military backgrounds to teach leadership principles.

Race, Risk and Different Realities

The mental health challenges facing boys vary significantly by race, requiring different approaches rather than universal solutions. Hispanic boys lose close emotional outlets as they age – those with a close confidant drop from 92% aged 15-17 to 75% aged 18-24, even as more friends confide in them about mental health.

Black boys face a growing social void. Loneliness among Black boys surges tenfold to 34% by ages 18-24, twice the rate of their White male peers. Despite initially being most likely to find peer conversations helpful at 91%, they experience the steepest decline to just 67% by young adulthood.

White boys show the largest disengagement from family support. Those who feel supported by family falls from 92% to 66%, while the perceived helpfulness of family conversations about mental health drops from 92% to 75%.

Blueprint for Action – What Should You Actually Do?

For men used to optimising everything from investment portfolios to fitness routines, supporting the mental health of boys and young men requires the same approach: identify what works, measure results and adapt methods based on data.

The evidence points to several practical interventions. Maintain direct, regular communication rather than relying on digital platforms. Research from Fatherhood.gov shows that active listening, emotional validation and direct man-to-man conversations create stronger outcomes than indirect approaches.

Keep communal rituals active even post-adolescence. The drop-off in group support effectiveness happens because these connections become less available, not less valuable. Top Blokes Foundation demonstrates how long-term mentoring programmes that emphasise positive masculinity maintain engagement through structured, consistent contact.

Focus on culturally responsive solutions rather than one-size-fits-all tools. The racial disparities in the Surgo Health data show that different groups need different support structures. Hispanic boys benefit from maintaining confidant relationships, Black boys need stronger social connections and White boys require sustained family engagement.

The Investment Mindset

Think of mental health support as asset management. You wouldn’t invest in underperforming funds simply because they’re popular. The same logic applies here: successful support requires understanding what young men actually find valuable, not what adults think they should find valuable.

The Journal of Adolescent Health research shows that reframing mental health as mental fitness and using positive masculine traits creates better engagement than traditional therapy approaches.

Small, personal changes have measurable impact. Whether you’re a father, mentor or business leader working with young men, the data shows that consistent, caring relationships with clear boundaries and emotional intelligence create the strongest foundations for mental health.

The next generation of young men isn’t broken – the systems designed to support them are. Instead of accepting the common view that men suffer in silence, fix the approach and you’ll see the results in everything from academic performance to leadership development. That’s an investment worth making.